Continuing the Schwerner Legacy

It only takes a little more than a couple of hours to get from Philadelphia, Mississippi to Indianola. But, that drive, just a short 125 miles, tells a tale of the history of social justice in our country and, along with it, the story of the role of Alpha Epsilon Pi Brothers can – and should – play in repairing our world.

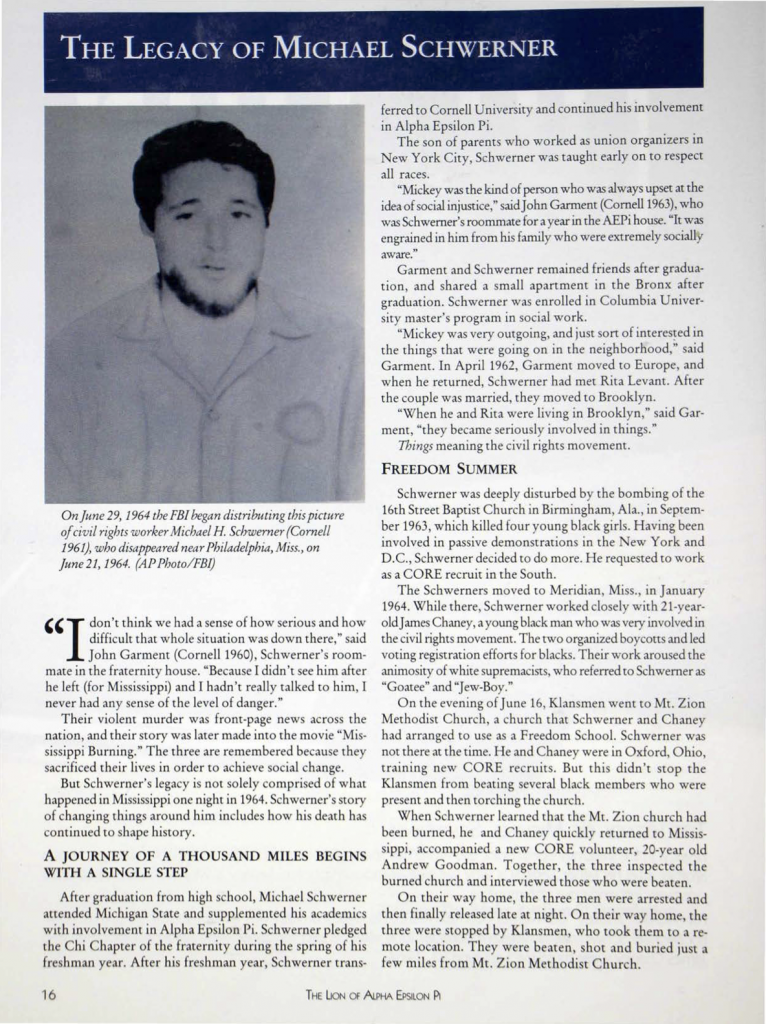

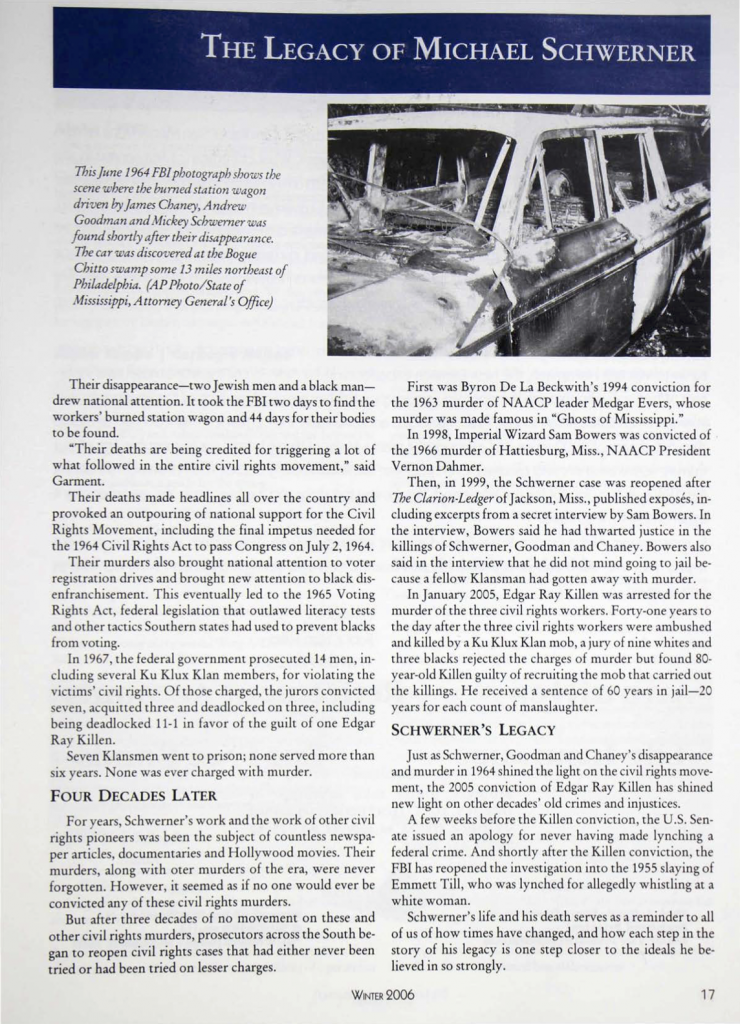

By now, it’s pretty well known what happened in Philadelphia, MS. In 1964, Brother Michael Schwerner (Cornell, 1961), along with two co-workers (James Chaney and Andrew Goodman) were killed by the Ku Klux Klan in response to their civil rights work, which including promoting voting registration among African American, most of whom had been disenfranchised in Mississippi since 1890. You can read more about Brother Schwerner and his story in the Lion article, reprinted from 2006, below. Brother Schwerner was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama in 2014.

Brother Schwerner set the stage for the next generation of activists and helped shine a light on an unimaginable life being lived in our own country. His story was commemorated in the Oscar nominated 1988 film, Mississippi Burning. His memory should be a blessing. His legacy as a hero and role model is secure.

But, travel North along Mississippi State Route 19 and West on MS-12. Travel through Mississippi towns like Ducant, Tchula, and Belzoni. Skip 56 years forward from 1964 as you drive. The cars have changed; the roadside diners and gas stations look different. The Mississippi Delta looks and feels a little different now. Where 19th century cotton plantations once were there are now empty buildings, created by large agribusiness corporations in the last century and subsequently abandoned as the economy moved elsewhere.

This is the highway into Sunflower County in Mississippi. This is the highway which tracks the legacy of Mickey Schwerner. When you get into Indianola, go a half mile past the B.B. King Museum (Indianola was the blues legend’s birthplace). Pull into city hall and ask to see the Mayor.

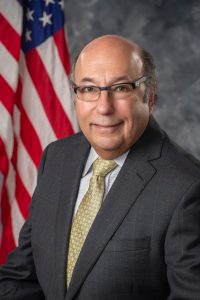

And there, likely wearing his trademark Hawaiian shirt, you’ll get to meet Brother Steve Rosenthal (Memphis, 1974). In a town which is nearly 80% Black, an AEPi Brother searches for racial and economic justice each day.

“My grandfather was a stowaway on a freighter from Lithuania in 1910. He eventually got a cart and his goods and worked his way down Highway 61 and came to Indianola in 1913. He became the local department in Indianola. I grew up here but always wanted to do something else,” said Brother Rosenthal.

“As a kid, I was shy. Painfully shy. Growing up Jewish in the strongly Christian-minded bible belt…my social skills weren’t the greatest. We knew that we were different. Not better than anyone because we’re Jewish but we knew we were different.”

In 1970, Brother Rosenthal left Indianola to attend Memphis State and study Industrial Engineering. “I was shy and small in stature. I was 4’ 10” and weighed 78 pounds when I got to Memphis State. Early my freshman year, I met David Fineberg. He could tell by the shoes I was wearing that I was out of place. He just took me by the hand and showed me the way. He said, ‘Us country boys have to stick together.’ Looking back, I think it is fair to say that I wouldn’t have survived at Memphis State if it wasn’t for AEPi. I was so used to being in the background, but they pushed me into leadership roles that without them, I never would have taken. I was even elected president of IFC one year.

One of Steve’s chapter Brothers was Sam Blustein who went on to become Supreme Master in 2010. “You knew Sam was going places. He was a great leader and one of the best people I knew. We always had the highest fraternity GPA but that was probably just because of Sam.”

At the time, Memphis State (now known as the University of Memphis) was gaining a national reputation. “I was pushed to become a leader by my Brothers but all of us thought we were going to change the world. When I walked into AEPi, most of our members were from New York and the east coast. We were very diverse, and I developed relationships with people who I never would have before without AEPi. Those relationship building skills were so important to me then…and still today. I came out of my shell and realized that I could thrive as a part of a team dedicated to making a difference for ourselves and everyone.

Our members had a bigger perspective than just the place we were at that point in time. That made me look bigger. I came home from college with a ponytail and I was a wild and crazy liberal. But, I saw, maybe clearer than ever before, the racial separation in my own hometown. I saw that, when our store was closed on Saturdays, the Black community could only go to other Black-owned businesses. No one else wanted them. And I realized how wrong it was.”

After graduation, Brother Rosenthal worked in retail management for several years but returned to Indianola when his father became ill. “I thought it would be temporary, but I never left.” He ran the family store until its closing in 2001 but he knew there was still more to do. “Being in retail in a small town, you can’t be political. But, enough was enough. After the store closed, I worked as a New York Life sales rep for eight years and I saw that I could make a difference in the community and verbalize my views.”

After the sitting Mayor raised his own salary by 60 percent, Brother Rosenthal took him on in the next election and won with 80 percent of the vote. And, he’s continued to win every year election since then.

Brother Steve Rosenthal

“I knew that I needed to create change in our community. We are the most impoverished areas of the most impoverished state in the country. This became my focus when I first got elected. We needed to bring up everyone. I heard about the Harlem Children’s Zone program in 2008 and it became a part of President Obama’s campaign. He started this idea of building Promise Communities and the Kellogg Foundation funded the concept. The idea is to teach and train participants to duplicate a pipeline of services. For example, starting with an expectant mother and making sure she is getting the care she needs and then, when she has the child, making sure the child is well cared for and given the programs they need. Look, we’ve never had a problem with a lack of programs, we just never connected them throughout the pipeline. (To learn more about this program, check out the 2010 documentary film, Waiting for Superman).

We applied to become a Promise Community in 2010 and in 2011, we got a call that we were one of 10 communities – and one of only two rural communities — in the country to receive funding.”

“This,” Brother Rosenthal says proudly, “will be one of my legacies. We did exactly what the program was designed to do. We got the program in place in 2012 and it now employs around 250 people – many of them are graduates of the program themselves. We’ve gotten two extensions of the program funding from the Kellogg Foundation.

You have to embrace the hardship to raise up the community. We all have to acknowledge our role in creating the hardship and recognize that we need to help make the changes necessary. Now, we’re focusing on improving literacy rates in my town.

A few years ago, our community had only a 60% pass rate for third grade literacy tests. That’s even after everything we had done with the Promise Community initiative. I believe that if you can read well, the other stuff is easy. We focused in on this problem. We got involved with Teach for America and we actually focused on trying to improve our system. We’ve turned it around. We’re at a 93% passing rate now.”

Fifty-six years have passed since Mickey Schwerner was killed for trying to register Black Americans to vote and 125 miles from where his body was found, one of his AEPi Brothers is creating a legacy in the community based in similar values. “Both of my kids (a son – and a fraternity Brother — and a daughter) live in Indianola now,” said Brother Rosenthal. “That’s my legacy. I’m working double hard to create opportunities for our children to want to come back here and call this home.

How can a white man keep getting elected Mayor? It boils down to relationships and taking care of people. That’s why I do this.”

“That sad history of Mickey Schwerner started right here in the Mississippi Delta. We were at the epicenter of the civil rights movement and all of the violence that came with it. But, I think one of the things I learned over the years and, especially, in AEPi is that if we make the world better, it makes us better.”

There are a lot of twists and turns on the road from Philadelphia to Indianola. But, even though there’s a lot of distance and time separating them, you can see the road stretch from one to the other.

Go back to cover