Alpha Epsilon Pi is proud to share this amazing story written by Brother Dale Schwartz (Georgia, 1965). Brother Schwartz began college at Vanderbilt University where he joined AEPi’s Tau Chapter in the fall of 1960. He transferred to the University of Georgia in 1962 and became active in the Omicron chapter of AEPi. He is a 1968 graduate of the University of Georgia School of Law. Brother Schwartz is the author of various articles on immigration law and has served as the National President of the American Immigration Lawyers Association (1986-87). He serves on a number of national boards of organizations concerned with immigration and refugee matters, and he has testified as an expert witness before committees of the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate on immigration legislation. He has been extensively honored for his contributions in the immigration law field and has been a frequent guest on national radio and television programs (Nightline, 60 Minutes, CNN, etc.).

Making a difference has been a way of life for Brother Schwartz throughout his career. He learned those lessons in Alpha Epsilon Pi.

Brother Dale Schwartz as a student in the 1960s

Sixty years ago, I was a freshman at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. A proud AEPi pledge, I was on “telephone duty” in the fraternity house when the phone rang. A young African American college student from Fisk University was calling Jewish fraternities to seek support for what later became known as a sit-in demonstration at a lunch counter downtown at Woolworth in Nashville. Students from (historically Black colleges) Fisk, Meharry Medical College, American Baptist Theological Seminary, Tennessee Agricultural & Industrial College and a local high school were to participate.

A short while earlier, in Greensboro, N.C., a group of young Black students demanded service at a segregated lunch counter in a Woolworth store. They were refused service but came back every day. Their efforts led to the sit-in movement across America and ultimately led — in no small measure — to the passage of the Public Accommodations Act by President Johnson.

Several of my AEPi Brothers and I thought it would be good to be there. So, on a Saturday just before noon, about 10 of our Brothers and New Members showed up at Woolworth in downtown Nashville. The Black students came in and sat down at the lunch counter and politely asked for menus. The waitresses were prepared and put up a CLOSED sign on the lunch counter. One of the waitresses poured a vanilla milkshake over the head of one of the students, turned around, and left. A few minutes later the Nashville police arrived. They mocked me and my Brothers and called us “Ni**er Lovers.”

Several of my AEPi Brothers and I thought it would be good to be there. So, on a Saturday just before noon, about 10 of our Brothers and New Members showed up at Woolworth in downtown Nashville. The Black students came in and sat down at the lunch counter and politely asked for menus. The waitresses were prepared and put up a CLOSED sign on the lunch counter. One of the waitresses poured a vanilla milkshake over the head of one of the students, turned around, and left. A few minutes later the Nashville police arrived. They mocked me and my Brothers and called us “Ni**er Lovers.”

Within an hour, probably due to the radio reports of the demonstration, the Klan wannabees showed up, mostly dressed in overalls and blue jeans, some with pints of whiskey sticking out of their back pockets. One short, fat white man walked up to the back of one of the young women sitting at the counter and put his lighted cigar into her back. To this day, I sometimes wake up at night remembering the sound of his hot cigar on her back—like a hamburger hitting the grill. Maybe I just imagine the sound, but it still seems real to me.

We jumped that man and beat him up. But the Klan types turned their full attention to beating us kids. I got hurt so badly that I was taken to Vanderbilt Hospital’s ER for treatment. The local policemen stood by, doing nothing to stop the beatings, and just laughed at us. Luckily, nothing on me was broken. My mother and father got to see me being beaten on the national network news that evening, as photographed by the local TV stations, which arrived shortly after the rednecks. The university threatened to kick us AEPi Brothers out of school for “inciting a riot.” We dared them to do that, and they backed down.

The Nashville sit-ins (as they became to be known) led to a boycott of Nashville merchants and demonstrations by thousands of local citizens. With the leadership of the Mayor of Nashville, the lunch counters and restaurants in Nashville agreed to provide service to Black customers. In many ways, this was the first seminal moment of the U.S. Civil Rights movement.

We didn’t know the names of any of the Black students at that lunch counter that day, but we will never forget their courage.

Turn the clock forward about 30 years…

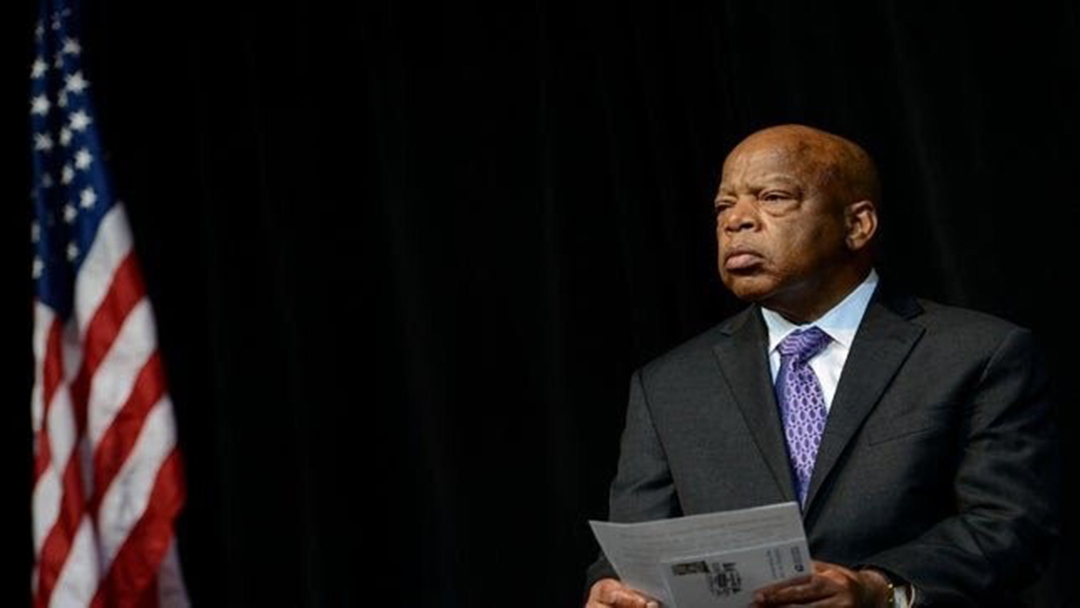

Brother Dale Schwartz

My law firm purchased a table at a birthday party and fundraiser for Congressman John Lewis at the Marriott Hotel in downtown Atlanta. I had known John Lewis quite well and had served on some Black-Jewish committees with him, as well as working on other legislative matters of concern to the Jewish community. Someone had put together a video of John’s life, from his preaching to the chickens on his family’s farm in Alabama to his rise to Congress. They found an old black and white film clip from one of the networks, and there I was, for all of two seconds on the screen, being beaten up. My wife let out a scream when she saw me, and John Lewis, who was sitting a few tables away from us, came right over to ask my wife what was wrong. When she told him, he asked us to stay after dinner ended.

When everyone else had left, John had the video technician run the video again and stop on the frame when my face appeared, replete with my pompadour and big, black Buddy Holly glasses. John hugged me and remarked that we had known each other for more than 30 years, but never realized we were together at that lunch counter in Nashville.

John looked at me and my wife and said, “Every Black politician in America claims he was at that lunch counter in Nashville, but I’m the only one with a white witness!” I will never forget that moment.

When my three daughters were little ones in school and went on field trips to Washington, they always visited Congressman Lewis. He was so gracious to the children and would introduce himself to each child and ask their names. If one said “Schwartz,” he would ask them if they were related to Dale Schwartz. Then, he would tell the kids that we were friends.

Last week, President Obama mentioned the Nashville lunch counter sit-in in his eulogy of John at his funeral. It made me remember this story and reminisce how, when John and I were together over the years, he mentioned to me that he would never forget how we Jews, and especially Jewish kids (and AEPi men), were the only ones they could turn to for support and help in those early days. I am proud that my AEPi Brothers joined me that day. None of us will ever forget that day, or the reasons we were there.

John Lewis was a small-in-stature person but, he was a giant among men. Rest in peace, my friend.